Ibrahim Sirkeci, Editor of Migration Letters journal

This short essay is designed to help a clear understanding of what key migration terms mean. Since it became a hit subject nowadays there is more and more confusion about what it is. As a professor of migration studies, I have always been asked this question, what is a refugee and what is a migrant. Although the answer looks simple, apparently it is not so for many.

If we start with the broadest term, that is mobility or human mobility. Mobility means any movement from one place to another. This includes people moving within the same neighbourhood, within the same region or province, within the same country as well as across national borders. All population movements as individuals or in groups fall under human mobility (or migration). Mobility has a more dynamic meaning allowing us to understand the open ended nature of migration process. However, migration has been a more commonly used term.

Population movements can also be differentiated into mass movements and individual movements. Mass movements are often driven by sudden external factors such as wars, intense conflicts, (environmental or man made) disasters. They may also follow international treaties or agreements as was the case in compulsory population exchanges between Turkey and other former Ottoman countries when the Empire collapsed in the 1920s. A more recent example is mass movement of Syrians in response to the war in their country started with the civil unrest in 2011. Other individual or group moves also fall under population movements. For example Mexican migration to the US or Turkish migration to Germany.

Migrations are often misleadingly treated as internal and international migration separately. Nevertheless, these two processes are closely linked. Internal migration means people moving within a country whereas international migration involves crossing international borders. One key problem with the meaning of migration is that it is closely associated with the old United Nations definition which suggests only those movements from one place to

Migrants, or movers as Jeff Cohen and I call them in our book Cultures of Migration (2011), are people who change their place of usual residence. This can be within their country of residence or they may relocate to another country. For administrative purposes, governments usually count only those change of residences only if they are for more than 12 months (sometimes more than 6 months). In principle, somebody’s usual place of residence is determined if he or she spends one night more than half of the year (180 days plus or 6 months plus). However, many more people move and spend substantial periods of time in other places.

People move for many reasons and often multiple factors contribute to the decision to move. Hence United Nations recently have begun using the category of “mixed migration” which simply means migrations due to multiple reasons including economics, politics, culture and else.

In our line of research over the years, we have developed a conflict model of migration which draws upon a very broad definition of conflict by Ralf Dahrendorf to include a wide range of situations from latent tensions and disagreements at one end to civil strife and wars on the other. Hence, we say migration is a function of conflict (i.e. discomforts, disagreements, tensions, dislikes, clashes, armed clashes, wars, etc.) or in other words, people do not move when they are comfortable and happy with, contempt with what they what they have and where they reside. Hence the term “forced migration” simply means “migration” as all migrations are one way or another and at varying degrees are forced. Whether people are pushed by states, armed organisations, or other groups is a matter of degree. In many cases, people feel insecure or at risk or dissatisfied and opt for migration. Although such moves are often labelled as voluntary migration, it is clear that the context, the circumstances, people around, and other actors and agents have an influence and bearing on such decisions to move.

Circular or pendulum migration refers to those moves, where people move for set periods of times to live and/or work elsewhere. One typical example for such moves is seasonal worker migrations. Often in agricultural sectors, migrant workers are brought in to help with the crops at various stages and at the end of the period (e.g. harvest) they go back to their usual places of residence.

Migrants (or movers) are the largest group covering all people who move from one place to another for short or long term residency. Holiday makers, tourists, travellers and/or visitors are excluded but they are also mobile and part of the human mobility. These latter groups do incur costs on administration and services but they do not have settlement purpose. Nevertheless, we should not forget the fact that there is a degree of fluidity between these visiting groups are more likely to become movers. They may be exposed to things and places so they can change plans and move. Among these groups, the exceptional migrants/movers arise whose moves are not initiated by a discomfort at the places of origin.

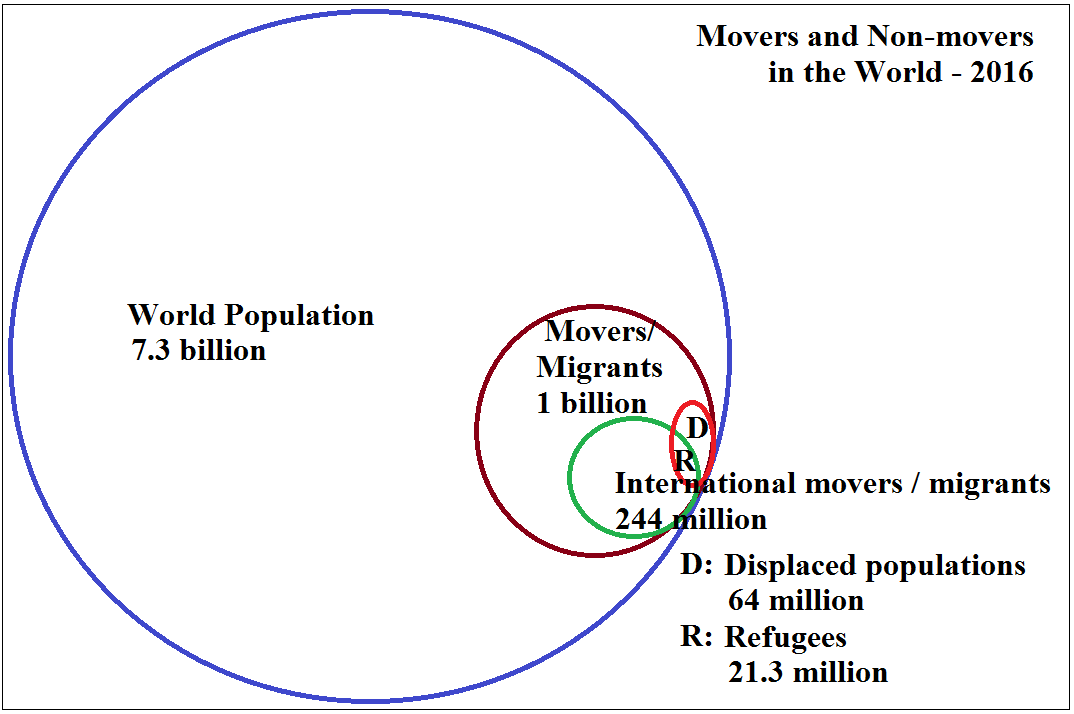

Among migrants/movers we have a larger segment of people who are internal movers, i.e. changing place of residence within a country. Among these internal movers, we also have internally displaced people who are in a refugee-like situation (i.e. in need of humanitarian protection). Internally displaced populations are estimated to be around 42 million world wide. Internal movers constitute about 10 percent of the population in the world.

The smaller segment among migrants/movers is international movers, whose population is estimated to be around 250 million world wide, representing about 3 percent of the world population. Key distinction for international movers is the fact that they cross international borders to change place of residence. Like the internal movers, international movers also contain about 21.3 million people who are in need of humanitarian protection and these are called refugees. Hence we should note that every refugee is a migrant/mover.

As of 2016, the largest group of refugees are of Syrian origin and Turkey host the largest number of refugees in the world. Refugees are different from other movers in the sense that they have to react to often suddenly arising political or environmental changes in their countries and seek refuge elsewhere without being able to resort to the means (social, economic, financial, political) they would otherwise do while also forced to respond and move relatively quickly. Often these moves happen in the form of mass population movements. Nevertheless, there are multitude of other situations where individuals or groups are targeted by those in power and they seek refuge in other countries individually and their moves can be lengthier and take place in a more planned fashion.

Those who perceive a risk, feel the threat of persecution because of their group identity, political views, beliefs or culture are called asylum seeker from the moment they depart and/or begin the application to seek refuge until their claim is officially recognised. Thus we can say refugees are a subset of asylum seekers who are a subset of international movers who are a subset of all movers.

There are all these other confusing terms about asylum seekers and refugees such as “guests”, “people in need of protection”, “people with humanitarian protection”, “under temporary protection”. These terms are usually employed by governments that either does not recognise the 1951 Geneva Convention for Refugees or those party to the Convention but with geographical restriction. Overall these confusing terms are political tools used by governments but they do not help us to understand the challenges, costs, and tragedies faced by movers under stress.